The more I read about identity in the modern West, the clearer it becomes that we are, frankly, strange—historically speaking. I’ve been reading Robert Bellah et. al. Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life. It’s a fascinating study of over 200 middle-class Americans from 1979-1984. It deals with what they value and pursue, along with their candid explanations or defenses for such values. Thus far, it’s reminded me of something Christians (especially those in the modern West) forget daily—a vice we’ve turned into a virtue: individualism, at its roots, is a heart-blinding evil.

Independence vs. Individualism

Understand that there’s a difference between some sense of independence and the ideological movement of individualism. We all need some level of independence to exist in the world, even though I’m convinced that we are designed to be dependent creatures. In other words, our dependence on God and others isn’t an effect of the fall. It’s simply how we’ve been made. Within this broader dependence, we acquire varying levels of relative independence in learning how to take care of ourselves and others.

But individualism is different. Individualism claims that each individual person, with his preferences and passions and values, is the highest end of society. The ultimate ethical rule of individualism is that “individuals should be able to pursue whatever they find rewarding, constrained only by the requirement that they not interfere with the ‘value systems’ of others” (p. 6). In other words, individualism assumes that isolated persons, with all of their subjective longings and judgements, are the end-all in a democratic society. Alexis Tocqueville wrote, “Individualism is a calm and considered feeling which disposes each citizen to isolate himself from the mass of his fellows and withdraw into the circle of family and friends; with this little society formed to his taste, he gladly leaves the greater society to look after itself” (quoted on p. 37).

The authors of the book break this down into two types.

Utilitarian individualism: You pursue your own best interests because that’s the most fulfilling life for you and others. You find your greatest happiness by doing so.

Expressive individualism: You should seek to express whatever sentiments or passions are inside you, ignoring any and all external restrictions.

But the authors of Habits of the Heart recognize even in their Preface that something is deeply wrong with this. They say that they are “concerned that this individualism may have grown cancerous” (p. xlviii). Indeed, it certainly seems that way. And the book was published in 1985, the year I was born. It’s 2024. Does rampant individualism seem to have taken over Western culture? Has it led to widespread isolation, misunderstanding, polarization, and tribalism?

The problem with individualism is that it encourages us to see ourselves not as we really are, but as we really aren’t.

And—here’s the critical question—has it blinded us to who we really are? I would argue the problem with individualism is that it encourages us to see ourselves not as we really are, but as we really aren’t.

Humans as Communion Seekers

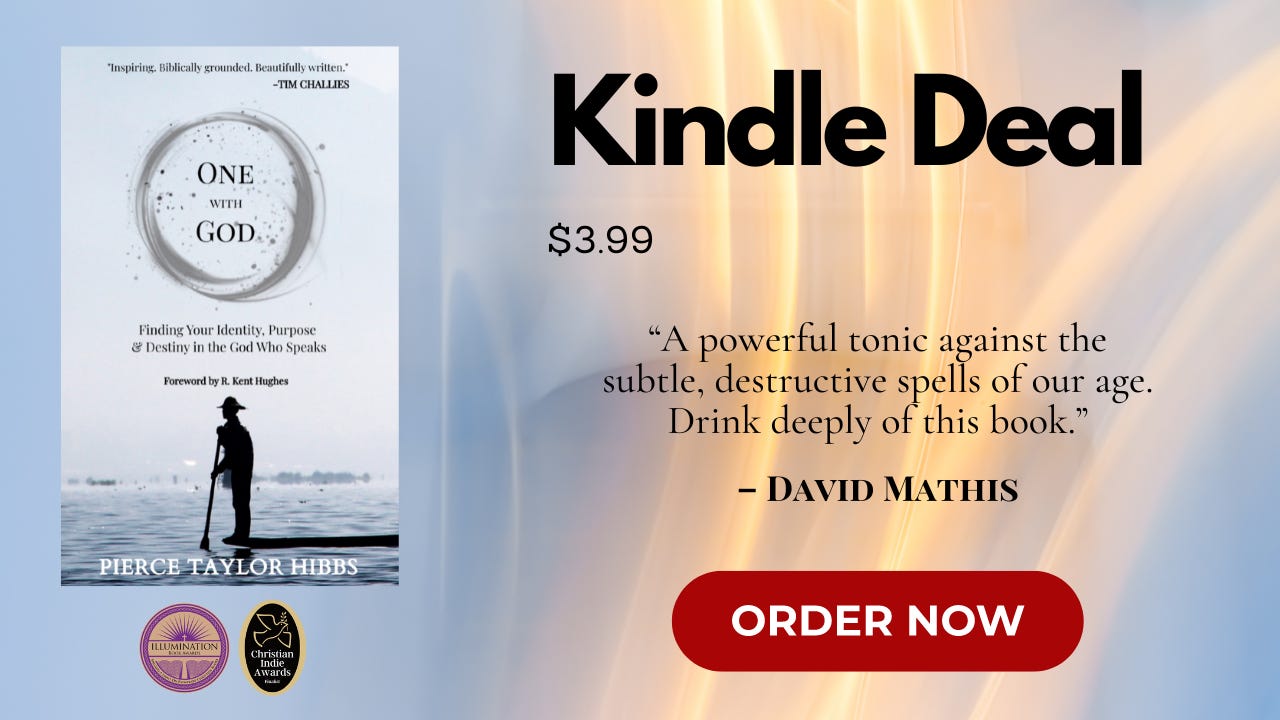

I’ve often written about humans as communion creatures. In Insider-Outsider, I use the term inside seekers. The principle is the same for both terms: we were custom-designed by a communicating God to be in communion with him and others. Relationship is central to our identity, not individualism (utilitarian or expressive). In fact, apart from our relationship with God, we will never fully know who we are and why we’re here (scroll down for the Kindle deal this month, which unpacks that more).

At our deepest level, each of us is leaning. We are born leaning. We live leaning. We die leaning. We never really stand up straight without any need for support. We weren’t made as free-standing Greco-Roman columns. We’re popsicle sticks. Stood on end, we’re bound to bend in one direction or another.

Why does this matter? Well, it shapes how we interact with other people each day—whether we seek to build others up with our words; whether we’re willing to accept help, or give it; whether we’re looking out for someone else’s good, regardless of that good involving us. How we see ourselves shapes how we engage with the world.

How we see ourselves shapes how we engage with the world.

Individualism sounds like an intellectual, conceptual movement, sort of like a low pressure system drifting through the cultural atmosphere—a neutral wave that we’ve all grown up riding, harmless as a breeze. It’s not. It’s darker than that. In encouraging us to view ourselves in isolation from others, individualism tears us away from our God-given mold, a relational mold, where we understand ourselves and others only in relationship to the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, the self-giving God.

The faster we run toward individualism, the more isolated and anxious we’ll become. Communion with God isn’t just an add-on to our spirituality. And communion with others isn’t optional either. We need these things. We’re made this way.

Who we are, why we’re here, and where we’re going is a matter of relationship.

Here’s to godly opposition to individualism.